As a senior at Kamehameha Schools in Hawaii, Koy-Allan Omo ’96 was looking for a sign. Like many at that stage in life, he faced the choice of where to attend college. He knew he wanted to go into education and be a coach. He knew he wanted to play sports and be at a small school. So when a Whittier College brochure arrived in the mail after he took the SAT, it felt like fate.

“And it just so happened that Whittier College started in 1887, and my school, Kamehameha Schools, started in 1887,” Omo said. “So that may have been some kind of high school senior type of thinking, but when you try to figure out where you’re going to go to school, you draw connections. And I thought, maybe I should consider Whittier College.

“It’s a school that has a lot of history. People would say, ‘Hey, you want to be a teacher. You should think about Whittier College. A lot of teachers came out of Whittier College.’”

Today, Whittier offers a bachelor’s in child development and an education specialist credential pathway to teach immediately after earning a bachelor’s, as well as a master’s in education. Of the students who come through Whittier to go into education, Lauren Swanson, department co-chair and associate professor of education and child development, said, “Their teaching journey is authentically personal. And they really, by and large, relish their time with their cohort and with their peers in classroom spaces, both when they’re going out into the K-12 world and in our own classrooms at Whittier.”

Swanson is proudest of what students take away when they leave Whittier: the ability to thrive as a team player in a field that is collaborative by nature. “There is a persistent myth of one teacher in the classroom, but education really is a team sport, a collaboration between grade levels and content areas, between gen ed and special education, administrators, teachers, staff, between parents and community members in schools. That’s how you make impactful learning experiences for students of any age. And so I’m humbled that that is the thing that we see as a department and as a college, and what alumni have pulled through into their own professions and spheres of influence.”

It’s a mentality and a methadology that guides many of the educators Whittier College has shaped, both within the walls of their own classrooms and well beyond.

The Beginning: Finding Whittier College

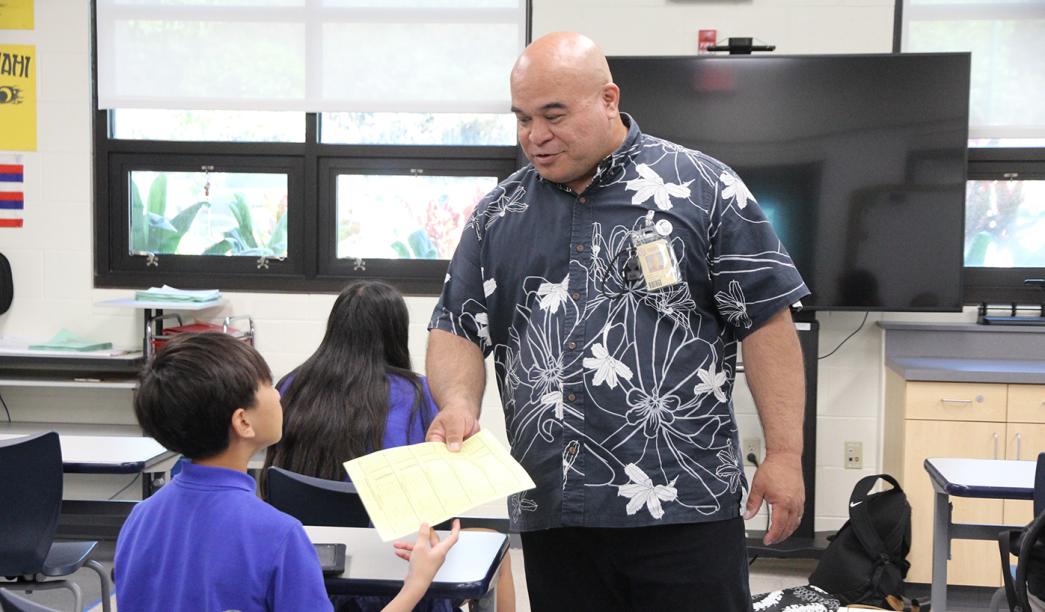

Omo tries to begin and end class with aloha. As much as it’s a part of his Hawaiian culture, it’s also about building relationships with his students. He’s been teaching for 29 years, today as a physical education and health teacher for seventh and eighth graders, as well as a football and track-and-field coach at Kamehameha Schools — his dream job since those days when he was applying for college.

“Through my years of teaching, I’ve built an understanding of who my seventh graders are, who my eighth graders are, and what they’re dealing with coming from elementary school and going to high school. And life as a middle schooler, as an adolescent, is tough enough, so I’m not trying to add on to that.”

After all, that individualized support characterized his experience at Whittier, both in the classroom and on the track and football field. “A lot of professors opened doors,” he said. “They were willing to talk academics as well as sports and current events. There was definitely a connection, building relationships, breaking the ice with storytelling and just building bridges with students. That’s what I’m trying to do: build a connection with the student at their level.”

He felt at home at Whittier, which, for many students, can be as integral to success as their coursework. He recalls how director of athletic recruitment and lacrosse coach Doug Locker “took care of the Hawaii guys.” Omo, for his part, was vice president of the Hawaiian Islanders Club, but Locker’s level of care and attention demonstrated the impact a teacher could have on a student.

“Whittier College gave me the degree, qualifications, experiences for me to be considered for this job,” Omo said. “I went further to University of Hawaii to get my master’s in education, but Whittier is where I cut my teeth.”

And now he can say, “I’ve taught long enough to start teaching the children of my former students, and I think I got a couple grandkids of my former students coming through shortly. So that proves longevity in an occupation where it’s very challenging every year. Every year is a little different. Kids are a little different. The problems are a little different. I’m here for the long haul. I just enjoy being in front of the students and helping them in their education. They’re a part of me as much as I’m a part of them.”

Applying the Whittier Philosophy in the Classroom

Like Omo, Swanson sees education as a vocation. “It feels fresh even when you’re doing it for a while because you always have a new class that comes together in a new way. It’s full of opportunities to stretch yourself, stretch your skill set, and stretch your goals.”

That’s what Danelle Almaraz ’90 has discovered in her career in education. She found her stride in the classroom teaching math and science at Hillview Middle School in Whittier for 20 years before moving up the administrative ladder, eventually becoming assistant superintendent of curriculum and instruction.

“I definitely am one of those people that knows that this is where I belong,” she said. “But now I teach adults. I teach district people, like superintendents, educational support people, the district office, and then principals.”

She does this as chief impact officer of InnovateEd, which works with districts across the United States and in Africa to develop long-term leadership standards that, in turn, secure better student outcomes. For Almaraz, the “right” leadership mindset promotes collaboration and curiosity; it’s “leading from the middle,” she said, where everyone is an equal player, and questions are asked without judgment or blame.

“Everything that we did at Whittier College helped me see that this was possible,” Almaraz continued. “It didn’t have to be a hierarchy of one person telling everyone what to do. It really could be a collaborative inquiry. It really could be something different. I remember going out and sitting under a tree or just doing things a little differently helped me see that in education, it was possible to learn and lead in different ways.”

Teaching was not always part of Almaraz’s plan as a student at Whittier. She graduated with a degree in math and went into accounting at first. “I’ve always loved numbers. I’ve loved math my whole life,” she said. “Once I got into doing the accounting work, I was coaching an all-girls basketball team in Lakewood and tutoring them because I wasn’t going to have a team for very long. Most of them were failing freshman algebra. That’s when I realized I loved teaching them algebra. I loved teaching math. I really liked seeing the way they think, not just what they know.”

She continued, “In high school and elementary, I was the kid who talked too much in class. I was the one that wanted to be asking questions, but it wasn’t until Whittier that I had professors that really enjoyed the curiosity. They love the talk, the dialogue. They really pushed and nourished that curiosity.”

Today, in her role with the school districts, Almaraz naturally leans into that curiosity.

It’s an approach she once had with her students, knowing that she appreciated it when her own professors took the same approach with her. “That was a good feeling, especially when you’re finding yourself and you’re open to trying new things.”

A Path to Leadership

Like for Almaraz, Whittier nurtured qualities in Troy Kimura ’94 that he didn’t know he had. His first year was rough: “I almost flunked out.” At the start, he was a music major, but by his sophomore year, he made a change. “I was in a music class my freshman year, and I was completely distracted. The windows were open, and I’m hearing this laughter. I’m hearing these kids playing. And I look out the window, and I see these preschool kids at Broadoaks School on Whittier’s campus. The music building sits adjacent to the preschool play yard. And so I said, Wow, that’s pretty cool.’”

So he got a work-study job at Broadoaks, the lab school, where Whittier undergraduates from different majors could observe classes and interact with teachers. Kimura fell in love with working with the preschoolers and even thought about opening his own preschool one day. He changed his major from music. “I received a teaching fellowship as an undergrad over at Broadoaks, and it gave me more responsibilities. I was able to be in the plan and implement things even as a college student,” Kimura said. “I went from a 1.3 GPA at the end of my freshman year to graduating at the top of my major as a senior in child development and elementary education.”

After graduation, Judith Wagner, the director of Broadoaks at the time, offered Kimura a graduate teaching fellowship. In that position, he helped open a fourth-grade classroom. He stayed on to open a fifth-grade classroom, then sixth, seventh, and eighth. He stayed at Broadoaks for about 30 years.

“My role over at Broadoaks continued to change,” Kimura said. “I became a credentialed teacher. I became a mentor teacher. I began supervising student teachers, training and working with the undergraduate and graduate students at the college. I even got to teach in the education department.

“One of the things that I really enjoyed was the fact that I got to not only work with and impact my students in the classroom, but I got to pour into and serve the undergraduate and graduate students as well that were pursuing a possible career in education or child psychology.”

Now, he’s in his second year as principal at Heights Christian School, a private Christian middle school in the Los Angeles area. He can’t help but attribute some of this success to Wagner.

“She was the one that offered me my first teaching job,” he said. “That’s one of the things about being part of such a small community. Your professors really get to know you as an individual, and they can identify and see things in you that you don’t see yourself.”

“I was that kid that was always in the principal’s office growing up. I was always in trouble. I shared that story with a couple of my sixth-grade classes this year, and one of my sixth graders said, ‘You’re still in the principal’s office every day.’ We got to laugh out of that. Honestly, I’m the least likely candidate to be doing what I’m doing, but I feel like it’s a calling that’s so much bigger than me. I cut my teeth in education at Broadoaks, and I was blessed to be able to spend nearly three decades there. But the work that I’m doing here is what I love, and it’s finally where my profession and my faith intersect.”

Embracing Quaker Values

Sandra Sanchez Thorstenson ’77 often thinks back to her days as a high school student in Whittier when reflecting on her role in education. “I was in what was termed regular classes at the time,” she said. “The expectations were not equally high for all students depending on your ZIP code and your socioeconomic demographic. About a month into my freshman year [in high school], I just thought, this is boring and not anywhere near as hard as I had anticipated.”

Thorstenson’s mother raised the issue with her school counselor, who then put her in the most rigorous courses. “I said to my dad, ‘I don’t feel like I belong,’ because there were no other kids from my neighborhood, and the demographic was very, very different in Whittier at that time,” she said. “I’m Latina. There were not very many Latinos, and certainly, they were not in the most rigorous courses. Thankfully, my mom spoke up. If she had not said anything, I would have never gone to college. And if my counselor had not followed up and put me in those most rigorous courses and checked on me periodically, I would not have gone to college. The teachers that I had were incredibly committed to ensuring that we had the preparation necessary to excel in college.”

She credits these teachers with inspiring her own career in education. As a superintendent of the Whittier Union High School District in the early 2000s, she shared this experience when she met with new teachers before the start of the school year. “The most important thing I wanted them to remember from my story was that they are never, ever to underestimate any student, and that they needed to understand that in our school district, we believe strongly that through the collective efficacy of all of our teachers and staff, we would be able to prove that demographics do not determine destiny.”

Thorstenson’s district did prove it. When she started as superintendent, Whittier Union High School District had a 35 percent gap between the lowest- and the highest-achieving kids across all the schools. “It was so much about demographics,” she said. “It was a collective for sure, all of us together, the faculty and the staff at all of our schools, with 13,000 teenagers at the time.” By her retirement in 2016, that gap fell to nine percent.

Thorstenson said they achieved this through a high level of collaboration and humility — and she considered herself a “reluctant administrator” when she first started taking on more traditional leadership roles. “I did not want to leave my classroom,” she said, adding that she started teaching U.S. history and world civilization right out of college. “I just felt like that’s what I was born to do, and that’s what I really was so passionate about.”

But she gamely took on each administrative role leading up to superintendent and her current role as a partner at Leadership Associates, which trains superintendents across California, with the mindset of a servant leader. “If someone is a servant leader, they understand that their role is not to be the boss of anyone, but to really be the team leader and to help lift everyone up and pull people together so they’re a part of decision-making.”

Thorstenson reflected that Whittier emulates these values of servant leadership. “The college has a wonderful Quaker history, which is right in line with the whole notion.”

As superintendent, Thorstenson found servant leaders in the Whittier students she worked with in the college and district partnerships. In one program, math and science majors from the college tutored high school students across the district; in another, college students who had been English language learners in their own youths mentored current English language learners.

“They were wonderful mentors. And that partnership was something that not only helped us with our achievement data, but just as importantly, if not more importantly, impacted the confidence of our students to have those role models working side by side with them.”

For all these reasons and more, Thorstenson said, “I am a proud Poet. I always knew that the education department was highly regarded, and I really did have a fabulous experience at Whittier College.”

Goes Far, Feels Funny

As Thorstenson reflects on her career, especially her superintendency, she cannot name a specific moment that has made her proudest; rather, she takes pride in the collaboration she fostered among her peers. It’s nothing she personally did, she said, other than reinforcing an organizational culture based on mutual respect and trust. As she’s moved on from the district into her new role at Leadership Associates, Thorstenson believes this vision has remained intact. “That’s what I’m proudest of, especially as that work continues.”

It’s a lesson in connecting the dots, in being that servant leader, that team player. “That’s what a lot of teaching is, giving a better understanding of some content or skill,” Koy Allen Omo said. “I always felt that I had a strength in connecting the dots, helping on the field or in the classroom.”

At this, Omo recalled one of his Whittier College football coach’s favorite rejoinders: “Goes far, feels funny.” “It means you’ve connected everything when you’re throwing,” Omo explained. “You did everything right. And when you get everything right, it really feels like you did nothing. That makes it feel funny, and that makes it go farther.”

It’s a catchphrase that Omo uses with his own football players today, and it’s a catchphrase that can, perhaps, apply to education. When teachers make those connections in and outside the classroom, as so many Whittier alumni over the years have demonstrated, their impact will go far.